Your Life Is the Supreme Meal

It’s easy to be grateful when you have a feast before you. But what about when your bowl is empty?

The chapter below is the third in a trilogy excerpted from Tap, Taste, Heal: Use Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) to Eat Joyfully and Love Your Body by yours truly, Marcella Friel, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2019 by Marcella Friel. Reprinted by permission of North Atlantic Books.

“Zen masters call a life that is lived fully, with nothing held back, ‘the supreme meal.’ And a person who lives such a life—a person who knows how to plan, cook, appreciate, serve, and offer the supreme meal of life—is called a Zen cook.”

–Bernie Glassman, roshi

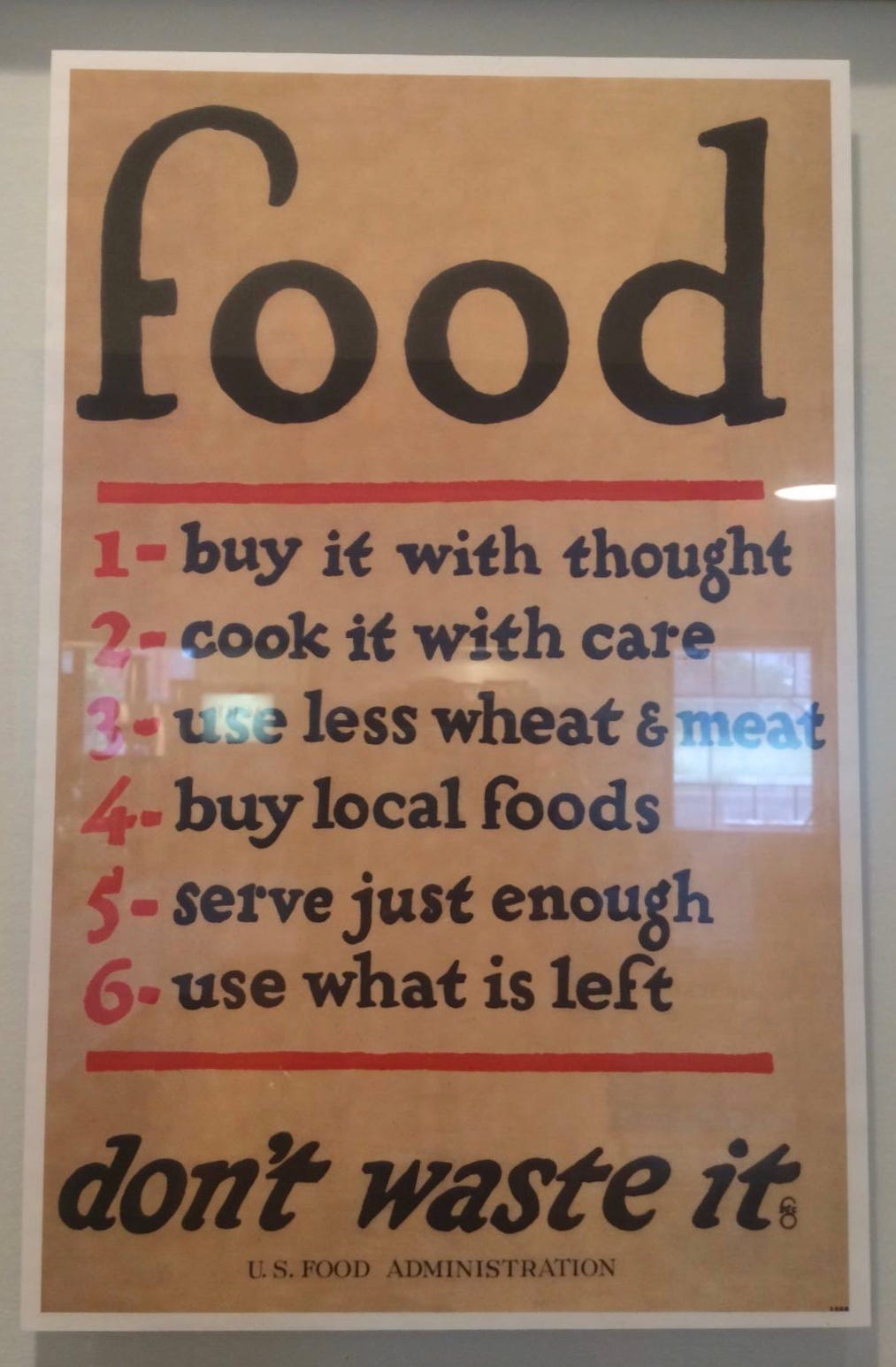

IN MODERN LIFE, our collective drug of choice is “more, better, cheaper, quicker.” In our frenzy to shield ourselves against any sharp edges of reality Mother Earth might send our way, we take refuge in efficiency, convenience, and speed at the expense of process, appreciation, and quality. We consume and toss not just food but entertainment, relationships, spirituality, perhaps even our own lives.

In a world where pleasure is commodified, joy is marketed, and eating is just a matter of shoveling in calories so we can get to the next thing on our list, our lives have degenerated into mere survival, rushing from one thing to another in an epidemic of “hurry sickness” that depletes our energy and ransacks Mother Earth’s natural generosity.

The epitome of this barbarianism is the drive-through meal. We don’t have to take time to get out of the car, sit at a table, be served, eat properly, and clean up, as our ancestors have done for centuries before us. We don’t have to be present to the food, to the hands that prepared it, to our bodies as we ingest it. When we’re done, we throw uneaten remains into the trash, along with the polymer packaging that will clog Mother Earth’s belly for the next half-million years. Everything is a means to an end that never arrives, until, one day, our body—and our planet—presents the bill.

Bottomless Bowls

Recently I had lunch with a friend; I ordered a Caesar salad with chicken. What arrived at the table was a mountain of romaine lettuce large enough to rival the fourteen-thousand-foot peaks in my Colorado backyard. This was not one, but at least six full portions of salad, intended for one person. I shrugged, sighed, ate a few forkfuls, and pushed the rest away. And no, I didn’t take a doggie bag of soggy lettuce home to sit in my fridge before I threw it out.

Leaving the restaurant, I sadly recalled meditation master Chögyam Trungpa’s words in his book Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior: “When people go to restaurants, often they are served giant platefuls of food, more than they can eat, to satisfy the giant desire of their minds. Their minds are stuffed just by the visual appearance of their giant steaks, their full plates.”

In our modern industrial food culture, we face a dilemma that our hunter-gatherer ancestors would have never imagined possible: the overabundance of food in supermarkets and the supersized portions at restaurants present us with more than we can possibly eat. In the United States and Canada, we throw out about 40 percent of the food on our plates (compared to 4 percent in sub-Saharan Africa). Globally, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, one out of three pounds of all food prepared for consumption on this planet is wasted. This global squander sends 3.3 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere and consumes about seven hundred square miles of water—an amount three times the size of Lake Geneva in Switzerland.

“Food waste—it’s kind of the tip of the iceberg,” says Jason Clay, a senior vice-president in charge of food policy at the World Wildlife Fund. And according to global climate activist Lynne Twist, we’re consuming planetary resources—soil and water specifically—50 percent faster than they can replenish themselves. Given these dire facts, and given the increasing temperatures and bizarre weather patterns we are now all experiencing, it’s absolutely time for us—right now, starting today—to make sure that the food we buy we will, in fact, eat.

It’s also high time to prevail upon the eateries we patronize to right-size their serving portions. Since the 1990s, portion sizes have doubled or tripled, a key factor contributing not only to global environmental devastation but also to the physical and emotional anguish of those who suffer from chronic, compulsive overeating and its myriad consequences. If I had that lunch with my friend to do again, I would have mentioned to my food server that the salad was way too big. Most retailers know that if five customers ask for something, it’s time to make a change. Let’s all be among those five and speak up.

In 2005, researchers at Cornell University’s Food Lab had fifty-four subjects eat soup. Half were served soup in normal bowls with normal portion sizes. The other half were served from a bowl that was imperceptibly, incrementally refilled through a tube beneath the table. The subjects who unknowingly ate from the self-refilling bowls consumed an average of 73 percent more soup without perceiving themselves as eating more or being more full than their counterparts.

When we eat from seemingly bottomless bowls of food, several things happen:

❧We eat from our eyes, not from our bellies. We let the amount of food on the plate, rather than our body, tell us how much we should eat. Our body’s satiety cues—the messages between brain and belly that say that we have had enough—go haywire. We lose our sense of where full ends and overstuffed begins.

❧We feel guilty. We’ve all heard the admonition, “Eat your food! There are children starving in the world!” If we have any social conscience at all, we feel the pain of inequitable food access and distribution around the planet. But overstuffing ourselves does not alleviate the hunger of others. As Frances Moore Lappé said in her classic book Diet for a Small Planet, hunger is not caused by lack of food but by lack of democracy. Eating more food than our bodies can handle is not the antidote to global starvation.

❧We get fatter. Marion Nestle, a professor of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University, positively correlates obesity rates with supersized food portions: “The larger portion business started at exactly the same time that obesity rates started to go up. … Muffins used to be one or two ounces; now they’re six or seven or eight. … When I was a kid, bagels were the size of what are now called mini-bagels. And you never used to go into a restaurant and be presented with a bowl of pasta that would feed six people.”

Perhaps the most tragic and pervasive consequence of our perpetual food surplus is that we don’t appreciate the food we have; we regard eating as more of a chore than a pleasure. If, as food journalist Michael Pollan says, “The banquet is in the first bite,” there’s no point in savoring our excessive fare if none of it is precious to us. “In the developed world, food is more abundant, but it costs much less,” says Rosa Rolle, an expert on food and waste at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, “but people don’t value food for what it represents.”

When society functions strictly on the basis of efficiency, everyone loses (except those who stand to profit from it, but even that’s only a short-term gain). And in a food system designed for us simply to stuff calories into our bodies, we are set up to become disembodied as we eat. Why bother to feed ourselves well or eat mindfully if the whole function of food is simply to overfill our guts? If the only purpose of food is to provide nutrition, why bother looking for the best meat, the best butter, the best vegetables? And if, indeed, you are what you eat, do you really want to be cheap, fast, and easy? And if not, what is the antidote?

The Deep Ecology of Gratitude

The more I look at appreciation and gratitude, the more I see them as the most ecological tools we have to heal not only our bodies but the entire planet. Appreciation and gratitude have a double-helix relationship—they augment each other. We can be grateful, for example, for the food we have in our lives, but when we slow down to appreciate the food—to notice the presentation, the aromas, the nutrition, the preparation, and the flavor—we amplify our gratitude by recognizing the myriad gifts good food brings us every day. Conversely, when we take time to consider why we’re grateful, we’re led inevitably to appreciate what we’re grateful for.

Before we get into any more mushy-gushy stuff about how wonderful these qualities are to cultivate, let’s look at them for a moment through their shadow side. Regret and resentment—the opposites of gratitude and appreciation—are easy, cheap, and everywhere, like junk food. Just as we throw away the drive-through packaging without a second thought, the energy of regret and resentment prompt us to see our lives only as waste to be discarded. “I’m a failure.” “I should have done it by now.” “What’s the use?” “It’s too late for me.” “I’m not worth it.” “It’s not worth it.” “Things will never get any better.” “If only [fill in the blank] hadn’t happened, my life would be fine.”

Instead of seeing the potential value in our experience, whether pleasurable or painful, we just want to get out of the pain, throw our experience away, get rid of it. We don’t care where it goes, as long as it’s not in our backyard. This is the same energy that litters highways, dumps poison into rivers, and causes us to trash and punish ourselves for what we see as our shortcomings.

If resentment is a form of energetic debt, as I described in chapter 11, then appreciation and gratitude are the means by which we increase our spiritual wealth portfolio and prepare the supreme meal that is our life.

Remember books we used to hold in our hands and read? Treat yourself to a good old-fashioned, copy of Tap, Taste, Heal to either keep for yourself or gift to a friend.

As a culture, we typically sequester our gratitude for Thanksgiving (which, curiously enough, is our national high holy day of overeating). We’re taught that gratitude means sitting around a table that’s overfull with food and giving thanks in the manner of a child petitioning Santa Claus: “Thank you, God, for this; Thank you, God, for that.” It’s easy to be grateful when you have a feast before you. But what about when your bowl is empty? How can we find gratitude and appreciation for something as painful as our food and body-love struggles?

In his early Buddhist teachings, Chögyam Trungpa wrote of “the manure of experience and the field of bodhi (or wakefulness)”:

Unskilled farmers throw out their rubbish and buy manure from other farmers; but skilled farmers collect their manure, in spite of the bad smell and the unclean work, and spread it on their land, and out of this they grow their crops.

If a person is skilled enough and patient enough to sift through his rubbish and study it thoroughly, he will … develop a positive outlook and create great wealth.

When you seek to effect change of any kind from a place of resentment, you are throwing away your rubbish and looking outside yourself to see if some other manure is better than what you already have. You’re adding more pollution to the problem. The path of appreciation, by contrast, teaches us how to become a skilled farmer of our own soul: how to use the manure of our experience to fertilize the soil that grows our crops, which we then use to prepare the supreme meal of our precious life. In the words of Bernie Glassman, coauthor of Instructions to the Cook: A Zen Master’s Lessons in Living a Life That Matters, “The supreme meal—your own life—is the greatest gift you can receive and the greatest offering you can make.”

How do we prepare such a meal? We begin with giving up our preferences for one kind of experience over another. We stop craving happiness and rejecting sadness and instead recognize, with an equal eye, that both have their merits and their drawbacks. We stop fighting ourselves and acknowledge what is. In the Zen cook’s language, we work with the ingredients in our pantry. Perhaps we open the cupboard, and all we see is sorrow, struggle, and loss. We can appreciate those bitter, pungent, and astringent flavors as wakeful contrasts to our incessant craving for sweetness, which lulls us to sleep and makes us allergic to discomfort and growth.

In the practice of Tapping, we say, “Even though I have this problem, I deeply and completely love and accept myself.” In the view of Tapping, self-love, self-appreciation, and self-acceptance are the antidotes to every stressful situation we can experience. Like a high-quality salt, appreciation harmonizes all the flavors of our life and brings out their most beneficial nutrients.

As our Tapping practice helps us grow into unconditional self-acceptance, we begin to see our struggles in a very different way. They shape-shift from a source of self-hatred to a rich, ripe, smelly, fertile gateway to wisdom and compassion.

As we dowse the wreckage of our traumas to reveal the gifts, blessings, and lessons within them, we come to appreciate that sometimes the worst things that we can experience are the greatest blessings in disguise. Had we thrown out our rubbish and bought our manure elsewhere, we would have squandered the wealth right in our own garden.

When our life becomes the supreme meal, we clean up. We appreciate ourselves enough not to gossip about our coworker; we appreciate ourselves enough to get to bed at a reasonable hour, so we can get up earlier and make a good breakfast; we appreciate ourselves enough to take the thirty-minute walk we’ve been promising ourselves; we appreciate ourselves enough to naturally abstain from that which does not serve us and to cultivate that which does. We realize, ultimately, that nothing—nothing—is ever out of place. Our entire journey becomes a sacred unity and thus worthy of our deepest reverence and gratitude.

Cultivating Food Peace and Body Love

There are many reasons why gratitude and appreciation are the key ingredients to your supreme meal:

❧Gratitude improves physical health. Negative emotions such as resentment and anger trigger the body’s inflammatory and stress responses, which, in turn, trigger food cravings and cause the body to hold on to excess weight. Gratitude, by contrast, cools the heat and inspires you to stretch yourself beyond these small-minded emotions and notch up your self-care.

❧Gratitude improves sleep. If you spend fifteen minutes at night journaling about what you’re grateful for from the day, chances are excellent your sleep will improve. And regular, restful sleep is one of the most important components of sustained and successful weight loss and mental well-being.

❧Gratitude improves self-esteem. You stop comparing your insides to others’ outsides and coming up better than or less than. Gratitude helps you find your right-sized place in your world, which can then translate into finding your right-sized physique.

❧Gratitude fosters resilience and reduces trauma. People who regularly express and experience appreciation have fewer PTSD symptoms and more resilience during stressful circumstances, which keeps every metabolic system in the body on even keel.

❧Gratitude magnetizes resources. As the saying goes, “You catch more bees with honey than you do with vinegar.” Gratitude delightfully sends friends, opportunities, money, and other auspicious conditions your way when you least expect them and most need them.

A Path to the Source

Perhaps the greatest benefit of practicing gratitude and appreciation is that they plug us into an ever-renewable bank of energy, a cup that always overflows and never runs dry. In twelve-step lingo, that energy is called “the God of Your Understanding,” which goes by many names:

❧Allah

❧The Angels

❧Atman

❧Buddha Nature

❧The Divine Mother

❧God

❧The Goddess

❧Great Spirit

❧HaShem

❧Higher Power

❧The Infinite

❧Source Energy

❧Spirit

❧Universal Love

❧The Unmanifest Absolute

Cultivating a consistent, conscious connection with this unseen animating force is, in my humble opinion, the single most powerful tool we have for finding hope in the rubble of despair, order in the wreckage of chaos, a way in the midst of no way. As Amma, the guru known for her life-changing hugs, likes to say, “Take one step toward God, and God takes one hundred steps toward you.”

Meal Prayers and Blessings

What better way, then, to heal our chronic afflictions with food than to invite that source energy, the God of Our Understanding, to join us at the dinner table? There is, ultimately, no better way to overcome unhealthy food behaviors than to practice sincere, mindful appreciation for your food in the form of meal prayers and blessings.

Addiction expert Gabor Maté points out that the ceremonial use of a substance is the direct opposite of the addictive use. Whereas food addictions reinforce our alienation in a hostile world, food rituals elevate our consciousness and celebrate our connection to a larger, benevolent universe. They also, according to chef and nutritionist Rebecca Katz, downshift our nervous system out of fight-or-flight mode and into a parasympathetic state, which makes our food easier to digest.

My favorite mealtime prayer is simply putting my hands on my heart, closing my eyes, and taking three deep, conscious breaths before I eat. Much like bowing before entering a meditation hall, such a gesture creates an energetic transition from everyday speed into sacred space. Spiritual traditions from every culture have beautiful meal prayers you can draw from if you need training wheels for this practice. You can also borrow this prayer I wrote for the first mindful-eating class I ever taught:

In this meal, the five elements offer themselves for my nourishment.

To the sun that provides light, warmth, and growth,

to the rain that replenishes and makes whole,

to the father wind that scatters the sacred seed,

to the mother earth that bears the seed in her fertile womb,

and to the space that gives birth to the dance of the elements,

I, your youngest daughter, offer thanks and praise.

On behalf of all sentient beings, I gratefully receive and enjoy this meal. Amen.

You’re also welcome to use the prayer my client Pam wrote. (As she noted, “You can’t shovel crap into your mouth after saying this!”):

“Before I was able to nourish myself, I was provided nourishment with great love and care. May I always love myself enough to give my body this gift of health and compassion. May I always respect the earth that provided this meal, and the hands that worked so hard to raise, grow, and shape the ingredients into the meal I am about to eat.”

I do encourage you, whenever you are ready, to write your own meal prayer. Say it at least once a day and see how it changes your relationship with your food.

“Golden Rules of Mindful Eating”: A talk I gave at the Denver Shambhala Center, 2015.

Simple Tools for Appreciative Eating

Once you have served the supreme meal, how do you eat it? Here are some tools for appreciative eating that I’ve cobbled together from various spiritual traditions. These guidelines bring peaceful delight to the table and have helped me and my clients reclaim sanity, choice, and dignity in our eating habits while cultivating love of our food and ourselves.

Eat food prepared by loving hands in a loving way.

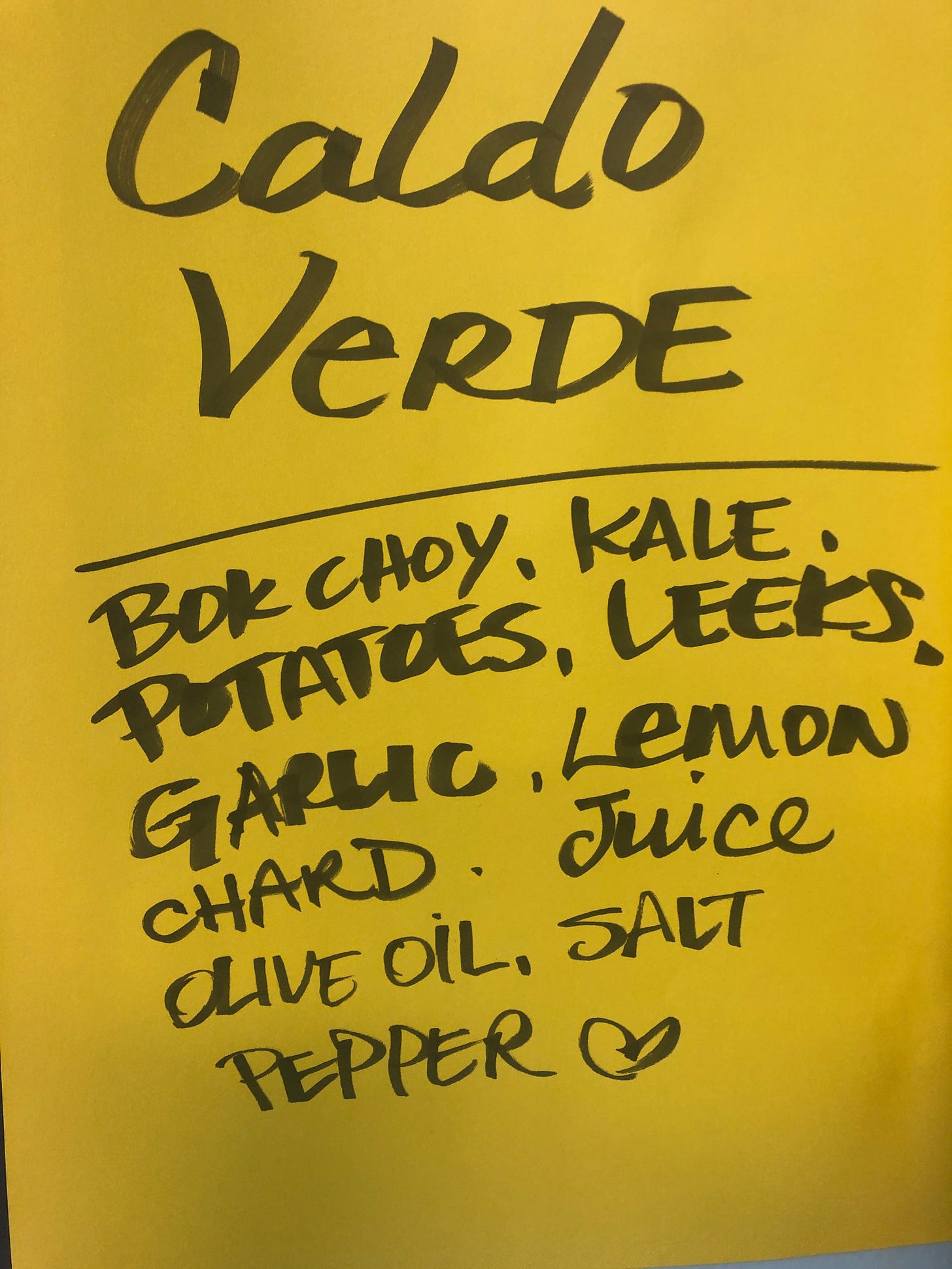

This rule is simple but not always easy. If you’re eating processed food, do you know whose hands—if anyone’s—prepared it? If you’re chronically dining on packaged foods or takeout, chances are human hands barely even touched what you eat. What kind of nourishment can you draw from such “food”—or rather, “foodlike products”—that are made by production machinery? Treat yourself to genuine nourishment. Eat at a local mom-and-pop restaurant instead of going to a fast-food joint. Visit a farmers’ market, join a CSA (community-supported agriculture) group, learn to cook a few simple things on your own, or ask friends and family to cook for you.

Pause before you eat.

Stop. Close your eyes. If it’s comfortable to do so, place your hands on your heart and take three deep, conscious breaths. If not, affirm your intention, through some sort of prayer, to eat consciously. Ask your body to help you recognize when you become full.

Put down your utensil between bites.

It takes about twenty minutes for the brain and belly to determine satiety, or fullness. Putting down your spoon, fork, or chopsticks causes you to slow down and chew, which activates the digestion process and helps your body to pay attention.

Practice hara hachi bu.

In the ancient Indian tradition of Ayurveda, the stomach is regarded as a cooking pot, and the digestive metabolism—agni, in Sanskrit—fires up that pot. When a cook makes a pot of soup, they have to leave space at the top of the pot, or else the agni doesn’t properly circulate, and the soup cooks unevenly. The same is true in our digestion. If we overeat, we can’t digest properly, and that produces what in Ayurveda is called ama, toxic by-products that give birth to degenerative disease.

The practice of mindful eating means reconnecting to that moment when our belly and brain say, in unison, “Enough.” The Japanese rule of mindful eating is hara hachi bu, or “Eight parts out of ten full.” While putting down your utensil, see if you can find that place where you are just full but not stuffed. Don’t worry if you can’t tell right away; keep practicing and reaffirming your desire to know, and it will come.

Take food with self-confidence.

Allow yourself to enjoy your food wholeheartedly. So often we eat from a place of conflicting emotions: “I want it. I know I shouldn’t have it. Who cares? I want it anyway!” What would it be like for you if, instead of saying to yourself, “I’ll never eat cake,” you could come to a place of having a purely free choice about eating the cake, and either enjoy it wholeheartedly or else let it be?

Take food in one place.

In the Zen tradition there’s a saying, “When you eat, just eat; when you sit, just sit.” The ideal posture of eating is sitting comfortably, with your focus on the food. If, by contrast, we’re eating while driving, in the Ayurvedic view that combination increases vata, or wind, which can blow out the agni of your digestive fire.

When we take food in one place, we might first encounter boredom, discomfort, and the strong impulse to check our email or read the paper. If this is so for you, I invite you to lean in to the sharp edge of those feelings. You probably won’t die from eating without diversion. Any process of healing demands of us that we enter the sanctuary of such feelings without needing to push them away. Breathing through the boredom and discomfort, we discover not only that we can survive but also that we meet a part of ourselves that has been waiting for us for a long, long time.

Enjoy your food.

Here you are, at the supreme meal of your life. Savor every bite. This moment is your feast.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Grief, Grit & Grace to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.