The chapter below is the first in a trilogy excerpted from Tap, Taste, Heal: Use Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) to Eat Joyfully and Love Your Body by yours truly, Marcella Friel, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2019 by Marcella Friel. Reprinted by permission of North Atlantic Books.

“The best and healthiest way to eat is to eat what nature dictates. The challenge is that we no longer live in a natural world, and navigating that is tricky.” —Sherry Strong

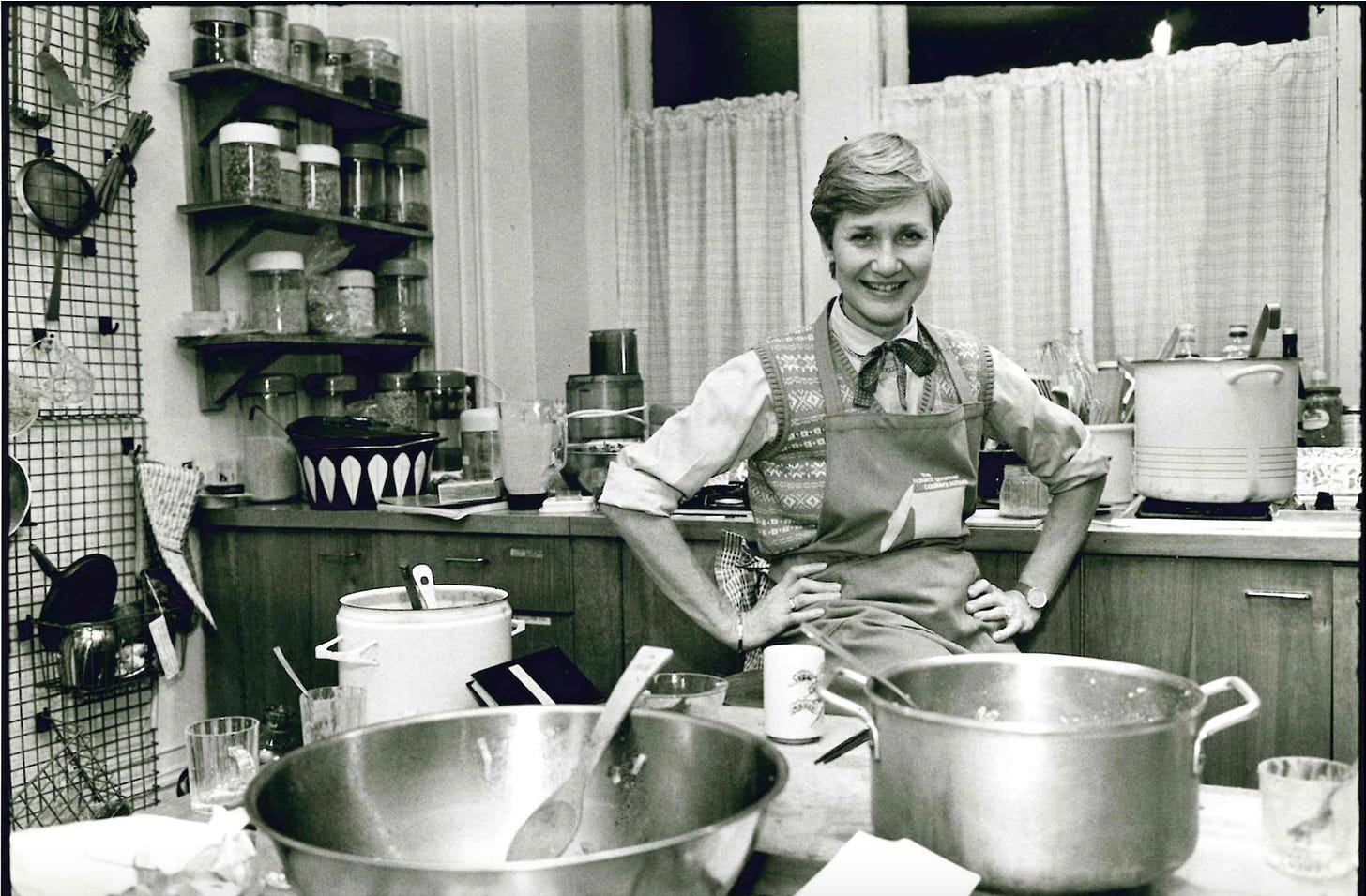

WHEN I WAS a culinary arts student at the Natural Gourmet Institute in New York City, I remember vividly a comment casually tossed out by my beloved mentor, Annemarie Colbin, that landed in my brain like a white-hot ember:

“Americans don’t eat food. They eat concepts.”

With her characteristic brilliance, Annemarie summed up our entire food crisis in seven words.

Food culture is the basis of all human culture. Long before supermarkets and food-processing factories, indigenous societies have been (and many still are) anchoring and organizing themselves around the tribal rituals of growing, hunting, harvesting, preparing, and eating food.

The reliability of those cycles—planting in the spring, tending in the summer, harvesting in the fall, and storing for the winter—connected human beings directly to each other and to the rhythms of nature. It created a sense of belonging both to the tribe and to the elemental forces that birthed the food on the table.

Just like Mama Bird dropping a worm in Baby Bird’s mouth, our female tribal elders—our mothers, aunties, and grandmas—traditionally fed us the foods that their intuition, observation, and direct experience had determined were best. They drew their knowledge from tribal foodways, the collective wisdom of a people as it pertains to food: which mushrooms nourish you and which ones kill you; which spices make beans more digestible; why tofu and seaweed combine well for both nutrition and taste. According to Zen chef Edward Espe Brown, those cultures that have preserved traditional foodways have the lowest occurrences of eating disorders.

“Conversely,” Brown explains, “we see that ours is a culture with few eating rituals and numerous disorders.” In modern industrial society, we’ve traded in Auntie and Grandma for celebrity chefs, television doctors, nutritionists, apps, recipe blogs, journalists, book authors (ahem), advertisers, food labels, and the latest diet craze.

As a result, we’re perpetually confused about what to eat. We judge what’s best for us not by listening to our bodies, but by what a celebrity television doctor says; not by how we feel, but by the grams of fat on the nutrition label; not by taste, but by abstractions, such as “60 percent protein, 30 percent carbs, and 10 percent fat.”

As Annemarie said, we rely more heavily on concepts than innate wisdom. As a result, we’re way too far out of our bodies and way too far up in our heads when it comes to having a clue about what’s for dinner. And as so few of us live on the land we came from, we eat a diet that’s not only radically different from our ancestral fare; it’s a diet that’s disembodied from Mother Earth herself.

This is not our fault. A little history might be helpful. Follow me for a moment as I lead you down the rabbit hole of how we got here.

Poisoned Roots

Have you ever had a conversation with someone that sounded like this?

I was drinking lots of milk to protect my bones against osteoporosis, like the articles I read in the women’s magazines recommend. But then I heard that too much milk drinking can actually lead to fractures. “Okay,” I said to myself, “then I’ll drink soymilk”—because soy is supposed to be good for women. But most soy now is GMO, so forget that. “Alrighty,” I thought, “I’ll switch to coconut milk.” I’ve been hearing all this cool stuff about how healthy coconut is. But now the American Heart Association says that coconut oil causes heart disease, so I’m not sure.…

This confusion isn’t you being dumb. It’s the result of the industrial food system’s efforts to keep your head continually spinning around what you should eat.

In the years following World War II, the US government funded the conversion of wartime chemicals to civilian agricultural use. Nerve gasses that once killed humans were converted to pesticides; ammonium nitrate, the main chemical used in bomb production, was repurposed as crop fertilizer. Armed with these new products and subsidized by citizen tax dollars, industrial farmers dramatically increased their yields of chemically addicted monocrops such as wheat, corn, and soybeans. With the government picking up the tab, corporate farmers were able to sell the grains for far less than it cost to grow them, which created a surplus that snaked its way up the processed food chain and spawned such dubious techno-foods as high-fructose corn syrup, denatured white flour, and refined soybean oil.

The excess commodity crops also were fed in abundance to cattle, hogs, and other agricultural animals, enabling Americans to eat an unprecedented average of a half-pound of meat per person per day. Thus the industrial farm gave birth to the industrial meat feedlot, with all its social and ecological fallout: groundwater pollution from waste runoff, the devastation of the small family farm and entire farm towns, and the overweight and obesity that cause manifold suffering for nearly 70 percent of the adult population in the United States.

Add the availability of cheap fossil fuels to the mix, and now you know why most people around the United States eat produce from California or Texas rather than nearby farms. The salmon on your dinner plate could be caught in Nova Scotia, shipped to China for processing, and then shipped again to the big-box grocery store on the outskirts of your town.

Don’t Be Fooled

The justification for this process comes from the food advertising industry, the mouthpiece of the industrial food production system. As no one in their right mind would eat such pseudo-foods if they knew the reality behind the products on their supermarket shelves, advertising provides the systematic and consistent manipulation of the consumer public to keep us betraying our bodies’ innate wisdom.

The industry’s primary tactic is to deflect consumer attention away from the processed condition of the food and keep it focused on individual nutrients as a bulwark of a product’s health-supportive properties. Marion Nestle, professor emerita of food studies at New York University, eloquently points out this phenomenon in her landmark book Food Politics:

“Tropicana, for example, promotes regular orange juice—unfortified—for its content of potassium (‘as much as a banana’) and Vitamin C (‘a full day’s supply’) and for its natural lack of saturated fats or cholesterol (which are found mainly or only in foods of animal origin).”

Nestle then cites Kellogg’s Nutri-Grain cereal’s health claim that it is “a good source of fiber,” about which the cereal adds, “a low-fat diet rich in foods with fiber may reduce the risk of some forms of cancer.”

What these promotions hide is that Tropicana orange juice made from concentrate can have a whopping twenty-two grams of sugar (five and a half teaspoons) per serving, and Nutri-Grain bars contain five different kinds of sugar (sugar, dextrose, fructose, corn syrup, and invert sugar), totaling eleven grams (nearly a tablespoon) per serving. The focus on individual nutrients hoodwinks unwitting consumers into believing that what they eat is, in fact, healthy, while concealing the natural nutrients that have been stripped out and the artificial ingredients that have been added, which leave the “food” essentially dead.

Nowhere is the advertising industry’s persuasive reach so perniciously demonstrated as in its quest to convert children into lifelong consumers. Eric Schlosser, author of Fast Food Nation (in my opinion, the best piece of investigative journalism since Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle), breaks it down this way:

“After largely ignoring children for years, Madison Avenue began [in the 1980s] to scrutinize and pursue them.… Hoping that nostalgic childhood memories of a brand will lead to a lifetime of purchases, companies now plan ‘cradle-to-grave’ advertising strategies. They have come to believe [that] … a person’s ‘brand loyalty’ may begin as early as the age of two. Indeed, market research has found that children often recognize a brand logo before they can recognize their own name.”

As children now spend more time screen watching than any other activity in their lives (other than sleep), advertisers can sink their hooks deep into a child’s subconscious mind and insidiously build strong brand preferences that influence parents’ purchasing choices. Young children (those in the hypnagogic state I referenced in the previous chapter) cannot differentiate advertising messages from program content; nor can they discern the persuasive intent of the ads themselves. Anyone with even an iota of ethics can see, then, that directing these messages at such a vulnerable audience is inherently exploitative.

The Cost of Cultural Rebellion

Industrial culture in general, and US culture in particular, prides itself on rebellion against culture. We Americans are a nation of innovators ever desiring to break old molds and make things better.

In doing so, however, we’ve thrown the baby out with the bath water in destroying the myriad fragile and gorgeous cultural customs that many of our ancestors brought to this land. If, indeed, we are what we eat, we Americans have become a people-less people whose wisdom roots have dissolved in the melting pot, and our distorted food choices reflect our collective alienation.

Divorced from the natural cycles and tribal activity that brought food to us in the past, our industrialized food system erases all context for our food beyond its appearance on the supermarket shelves or in the fast-food menu. That lack of context leaves us prone to food addiction, compulsive overeating, and degenerative disease. The longer the chain between Mother Earth and our food table, the more confused and disembodied our food choices become.

As a granddaughter of Sicilian immigrants who arrived in the United States via Ellis Island, I was blessed to grow up in this country with elders from il vecchio paese who imparted on me some of their wisdom foodways. With my father long gone and my mother single-handedly raising five children, my grandparents’ home down the street was my day-care center. My grandfather was a consummate gardener, my grandmother an admirable cook. It was at Grandmom Marrone’s table that I learned, as early as age four, how to roll pizza dough, grind sausage meat, and pick vegetables from the garden. Because I was continually exposed to fresh, homemade foods, I also developed early on the palate to appreciate distinctive and life-affirming flavors: the piercing bitterness of dandelion, the mild reassurance of zucchini, the deliciously excremental aroma of naturally aged cheeses and cured meats. I learned as a young child the fundaments of feeding myself well and eating good food, so that, even as I wrestled with sugar addiction in my midthirties, I was able to draw on the skill set that was embedded in my gustatory DNA, thanks to Grandmom and Grandpop Marrone.

My earliest food memory is of the strawberry patch that bordered the well-manicured lawn of my grandparents’ garden. In Grandmom’s pink Bakelite bowl I remember staring in anticipatory awe at a cluster of feisty ruby-red strawberries on the verge of spilling their juices. When Grandmom poured in the cream from her pitcher and kissed the bowl with a delicate sprinkle of sugar, I slowly stirred the cream and berries together, watching the red berry ink shamelessly swirl around the dignified cream. My grandfather, seeing my fascination, remarked, “If you keep eating so many berries, the tip of your nose is going to turn into a little strawberry!”

“I wonder how that could happen,” I mused, while pondering the red, white, and pink frenzy my delicious treat had become.

As immigrants, my grandparents were always aware of their position as outsiders in mainstream society, and so it was supremely important to them that their children and grandchildren assimilate. Even as we spoke at home in a pidgin Sicilian dialect, they always reminded us that, as americani, our survival imperative in the New World was to leave the garden zucchini and dandelion behind and opt instead for the frozen Green Giant Le Sueur peas that came from who knows where.

Creating a New Food Culture

While we might feel a poignant nostalgia for the foodways of our ancestors, most of us living in modern society aren’t quite ready to chuck it all overboard for a back-to-the-land lifestyle. How do we, then, invoke our ancestral wisdom to guide us in good food choices as we navigate the labyrinth of confusion?

Annemarie Colbin, once again, had the answer. Below are her Seven Criteria for Whole Foods Selection, a fad-proof set of guidelines to help you cut through the endless contradictory information churned out by the industrial food system and crack the code on that ever-vexing question, “What in heaven’s name should I eat?”

The criteria that follow are meant to be broad guidelines for how to think about the food on your plate. They are not meant to become something you flagellate yourself with because you ate a salad in the wintertime. Be reasonable. If you apply these criteria to your food choices, you’ll find yourself naturally making wiser decisions regardless of whatever food plan you’re following.

Seven Criteria of Whole Foods Selection

Whenever possible, choose foods that are

❧Whole: Ideally, all the edible parts of the food are intact: eggs with yolks, chicken with skin and bones, oranges with pulp, rice with bran and germ. Food that has all or most of its edible parts intact has both greater nutritional synergy and more satisfying flavor.

❧Natural: As Mother Nature intended it: as minimally processed as possible. This means staying away from commercially canned, genetically modified, irradiated, artificially colored, and chemically preserved food-like products. When it comes to reading food labels, a good rule of thumb is, “If you can’t pronounce it or don’t recognize it as food, don’t eat it.”

❧Local: How “local” is local is up to you. My definition is not more than a day’s drive from where I live. If my food needs to get on a plane, train, or rig to reach me, it’s not my first choice.

❧Seasonal: For most of us in the broad equatorial region of the planet (and climate upheaval notwithstanding), this means sprouts, shoots, and stems in the spring, leaves and fruits in the summer and fall, and roots in the winter. It means eating fresher, less-cooked foods in the warmer months and naturally preserved and slower-cooked foods when it’s cooler outside.

❧Appropriate: This has to do with eating in accordance with your constitution. If your forebears hail from the Mediterranean, you are most likely adapted to a broad fare of fresh vegetables and fruits, whole grains, and animal foods in moderation. If your ancestral line traces back to South Asia, you’ll want to stick with whole grains and pulses embellished by occasional meats, fresh tropical fruits, and fermented dairy. Those few who hail from the polar regions of the planet, where arable land is scarce, might not have the guts (literally) to digest fibrous plant foods and might be better off sticking primarily to meats and animal fats.

❧Balanced: Look at the food you eat at any given meal. Do the colors on your plate appeal to you visually? Which colors, if any, are missing? Is there a diversity of textures, a balance of raw and cooked, of fermented and fresh? You might not eat a balanced meal one day, but if you seek to balance your overall food intake according to this principle, you will get all the nutrients you need, not to mention the satisfaction of the food itself.

❧Delicious: This is the most important point of all. If it’s not delicious, why eat it? Let’s be done with that grim “eat-it-it’s-good-for-you” ethic from the hippie health-food days. We have lots and lots of ways nowadays to make food both yummy and healthy. And, as all wisdom food traditions know, pleasure is a must when it comes to eating well. So let’s make it delicious above all.

Remember: This is about progress, not perfection. The only way to do this 100 percent perfectly is to grow your own vegetables, grains, and fruits in a garden or orchard and raise your own animals for meat and eggs. Beyond that, there will always be some degree of compromise. How much you compromise, though, is up to you.

Out of the Supermarket, into Your Community

One easy (and fun) way to reduce confusion around your food choices is to stop relying on big-box supermarkets as your primary food source and get acquainted with the alternative food supply chains that might well be right under your nose.

This might take some effort—you might have to restructure your schedule or walk a few extra blocks or drive to a town out of your way or get off at the next subway stop—but the myriad dividends you’ll receive in return will be more than worth it.

Farmers’ Markets

Among the many, many reasons to support local farmers’ markets, here are a few of them:

❧Farmers’ markets build community. Strolling around an open-air market brimming with vibrant seasonal foods, you’re not only getting easy exercise, but you’re also running into folks from town, getting the latest news, and making new friends, some of whom might be the farmers themselves. Back at home, your belly will remember the farmer’s smile as he handed you that juicy peach. A bar-scan code just can’t give you that kind of love.

❧Farmers’ markets support the local economy. If you stop shopping at the mega grocery store on the outskirts of town, chances are no one would even notice you were gone. If you bring even a fraction of those food dollars to your farmers’ market, you’re helping farmers keep their farms alive to supply the freshest food money can buy, usually at a reasonable price. Recycling your food dollar in the local economy makes everyone richer. (Hint: If you’re short on cash, go to the market a half hour or so before closing. Farmers are often happy to give you extra—for them it’s less food they have to reload onto the truck and take home, and for you it stretches your food dollar. Everyone wins, once again.)

❧Farmers’ markets have higher-quality food. At your local market you’ll find a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, and heirloom meats that you cannot find in big stores, because the varieties themselves don’t hold up to industrial production. Many foods in farmers’ markets were harvested just that morning, as opposed to sitting in refrigerated warehouses for weeks on end, like much of the produce in the big-box stores. Ranchers who raise pastured meats often give their animals happy, healthy lives and are committed to sustainable and humane animal-husbandry practices. And then there’s the flavor—ah, the flavor!—you will remember the real tang of a sun-ripened strawberry, the sweetness of summer corn, the tomatoes that make a mess on your cutting board at home, because they can’t help but share their juices all over the place. This is what food is supposed to be, people!

Community-Supported Agriculture

Also known as subscription agriculture, community-supported agriculture (CSA) differs from farmers’ markets in that you purchase a portion of a farm’s harvest in advance and then share in both the risk and the reward. The Japanese call this system teikei, which means “farming with a face on it.” The win-win of a CSA is that you have “food in the bank” for several months, while farmers receive the income they need up front for hiring labor, repairing equipment, purchasing seeds, and so on. Many CSAs also ask that you contribute some volunteer hours to help distribute the food, which nourishes and restores that age-old link of food culture and the human community.

Community Gardening

If you have a green thumb (or would like to cultivate one), community gardening is a great way to build food self-sufficiency while learning new skills (or honing your old ones). Community gardens are an especially powerful vehicle of renewal in urban lower-income neighborhoods, where blighted vacant lots are transformed into patches of paradise, providing abundant health-supportive foods for local residents and raising the quality of living for entire communities.

Smaller Local Markets

When you do have to go to a supermarket, go out of your way to look for the little health-food stores and smaller markets downtown. As with the farmers’ markets, CSAs, and community gardens, you’ll get to know the folks who work there. The food quality is likely to be fresher and better. The experience is less stressful. And you’re keeping your food dollar circulating in the local community economy. For all you know, the owner of that store is a single mom supporting three kids. Wouldn’t you rather support her than some corporate big shot in a city far away?

A Final Word

With food, as with everything else, you get what you pay for. If you’re thinking to yourself, “Yes, but this food is so expensive,” consider this: we here in the United States spend less per capita on our food than any other nation—but we pay the high price of low cost in our soaring rates of degenerative disease.

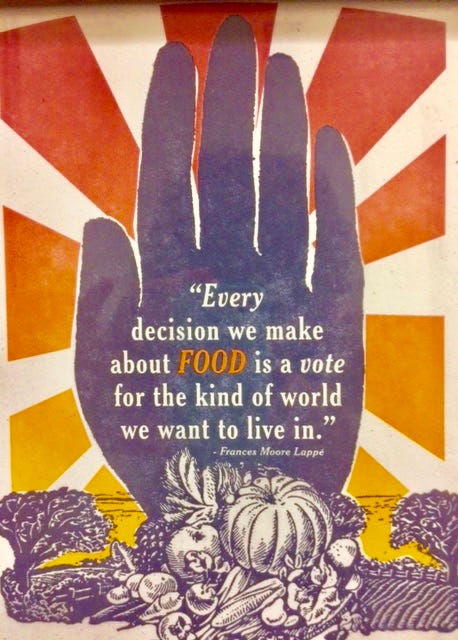

For decades, the industrial food system has been hell-bent on proliferating obscene amounts of cheap food that makes us sick. Take your power back, vote with your wallet, and rewrite your contract with that system. You will be better off paying the farmer than the doctor.

Loved your reading—your acknowledging giggle and tonal excitement about ripe garden gifts.