The day I decided never to see my mother again

Reflections on the taboo of mother-daughter estrangement

According to Tibetan Buddhist teachings, we have all been each others’ mothers in our millions of past lives.

Therefore we should regard all beings we encounter today—down to the tiniest insect—with the same lovingkindness we would extend to our mothers in this lifetime.

The spiritual precept of honoring Mom—and Dad—isn’t unique to Buddhism. The Ten Commandments of Judeo-Christianity exhort us to “honor thy father and mother,” while indigenous traditions across the globe practice ancestor worship to help ensure abundant harvests, financial prosperity, and peaceful relations with neighboring tribes.

In Islam it’s said that “Allah will maintain relations with those who are good to their families and will cut off those who sever relations with their families.”

I suppose then, from that point of view, the fires of eternal damnation await me after my departure from this life because, about two years before my mother died, I decided—or rather, the decision made me—that I would never see her in person again.

Even now—nearly 15 years later—I know that was the wisest choice I could make in response to a question that vexed me to my core:

How do I “honor my mother” when my mother is less than honorable?

What does it mean, I wondered, to “honor my mother” when Mom is flush-faced screaming at the top of her lungs, “You goddamn son-of-a-bitch kids, I wish you were never born!”?

What does it mean to “honor my mother” when, as an 8-year-old, I watched her hatchet down the bathroom door after my sister locked herself in to save her life?

How do I uphold this noble precept after seeing bright red blood splayed across the white kitchen-wall tile after she backhanded my brother across the room?

The only answer that made sense to me—then and now—is that we honor such mothers as these by summoning the courage to tell the story, with utmost compassion for them—and for ourselves.

This then, in honor of my mother, Anna Marrone Friel (1928-2009).

Lest I portray my mother as a complete monster, let me begin by saying that she, like all of us, had mixed traits.

My sweetest memories of her rest in the mirror of my mind against the turbulent backdrop of the late 1960s, when as a little girl I watched MLK’s funeral and RFK’s assassination on my grandmother’s black-and-white TV in our Italian-American suburb of Philadelphia (where racial violence and police brutality roiled the city much like Johannesburg).

While the world raged around us, Mommy and I would dance in the kitchen together to her favorite “Friday with Frank” and “Sunday with Sinatra” shows on WPEN Philadelphia FM radio. We’d point to each other wide-eyed and sing “That’s why the lady is a tramp” while making Italian pizzelle waffle cookies at Christmastime.

Among her five children, I shared with Mom a unique ecosystem of songs, jokes, and hugs. Her nicknames for me included Monkey Face, Funny Face, Pumpkin Pie, and Kitten, the first two capturing her amusement at my clownish ability to mimic anyone, especially her.

All the affection, play, and intimacy notwithstanding, I tip-toed across the eggshells of my early years in a perpetual inhale, knowing any fun we had would inevitably shatter into one of her rageaholic screaming frenzies.

Most humiliating among these were those sticky, sweltering summer nights, with house windows hoisted open to receive any breeze that God in His mercy would bestow on us, where my brother would beseech her, “Mom, stop! All the neighbors can hear you!”

To spite him, she would go to the window and scream, to his scalding horror, “I don’t give a shit who hears me! Go to hell you little bastard!”

Around age 13 I gave serious thought to running away—for about 10 minutes. Quickly realizing it wasn’t a great idea, I determined instead to hunker down, wait it out, and cross the threshold of freedom that awaited me at legal adulthood.

When I turned 18, Mom gave me $750 and a kiss on the cheek.

With those provisions in tow, I bolted from home like a bullet from a gunbarrel and headed to New England for college.

Over the arc of my young adulthood, my quest to heal the scourges of my mother’s emotional violence carried me across portals of consciousness that were nowhere on the horizon of my Philly childhood.

Foremost among them was the practice and study of Tibetan Buddhism I began at age 25 that included hours of tonglen meditation—reversing the “you-owe-me” logic of my bitter, victimized heart by breathing in (rather than resisting) my mother’s hateful words and breathing out my wish for her deepest peace and well-being.

I entered 12-step recovery, did years of talk therapy, beat pillows, screamed and sobbed and raged—all in pursuit of the holy balm that would pacify my blistered and aching soul.

Despite those efforts to forgive my mother, forgiveness happened anyway.

One weekend afternoon in the late 1990s, I walked through the door of my mother’s house on a weekend furlough from my work in New York City teaching cooking skills to low-income adults.

After working in every so-called “bad” neighborhood of NYC with adults recovering from homelessness, adults living with AIDS, adults with eight teeth in their heads and 4th-grade educations, adults who skulked the borderlands of life’s good fortunes—a flash of realization bolted through my being as Mommy greeted me at the door:

She was just like one of my students.

Like them, she had eight teeth in her head and a 4th-grade education.

Like them, she got dealt the cards from the bottom of the deck.

Her shitty parenting was never a matter of intention. It was a matter of capacity.

She truly—truly—tried her best.

If she could have done better, she surely would have.

There was no pity for either her or me in this realization.

It was a stunningly simple fact that evaporated my resentment into space.

At that moment, I completely ceased to expect anything more from her to make my life better.

All judgment of her fell away as I fully accepted her—and even celebrated her— exactly as she was.

This wasn’t the forgiveness I had expected.

Up until that moment, I thought that forgiving my mother meant that the heavens would open and the angels would sing as I blithely glossed over the past in a euphoric haze of denial and erasure.

This forgiveness, instead, was as prosaic as paying a past-due bill.

It was an act of bringing my emotional currency into present time by releasing the expectation that she would ever become the mother I had been waiting and hoping for her to be.

It meant a permanent ceasefire in the losing battle to make my childhood what I thought it should have been.

In so doing, through the grace of That Which Is Greater Than My Own Being, I cashed in my bankrupt demand for justice and invested my emotional wealth in the mercy of accepting things as they are.

That included accepting—but not tolerating—her continued abuse.

Among my mother’s many tactics to wreak emotional havoc with her children, foremost among them was violently expelling us from her house at the slightest perceived transgression on our part.

It became so commonplace among my four siblings and me it was like another weary headline in the daily news. We’d roll our eyes and sigh, “Oh so today it was your turn to get kicked out, huh?”

By the early 2000s my mother’s health on every level precipitously declined, most likely due to the fistfuls of painkillers she routinely swallowed to palliate her somatized mental anguish.

Thanks to the marvels of pharmaceutical science, Mom got sicker and sicker the more docs she saw and the more meds she took.

And so the day came, around 2007, where I can’t even remember what we were bickering about, but something pulled that hair-trigger of hers, and she yelled at me, “Get the hell out of my house, you little bitch!”

My response was quite spontaneous. “Mom,” I said calmly, “Are you sure you want me to leave? Because if I do, I’m not coming back.”

Her yell escalated to a shrill scream: “Get out!!”

So I did. I walked out the door and never went back.

And in that moment I realized that I could forgive her and never want to see her again.

I could forgive her and still need to set boundaries around when, how, and whether I interacted with her.

This was a nuanced Middle Way between mom-bashing / mom-trashing on the one hand and being a complete doormat on the other.

It was a tightrope walk of loving her as she is while not sweeping the damage under the rug.

It was also a living amends to myself by honoring that I was no longer willing to finance the emotional costs of continued mistreatment at her hands.

It’s okay to take care of yourself when Mom is toxic.

Here’s what mother-daughter guru Bethany Webster has to say about daughters going no-contact with Mom:

“Estrangement doesn’t necessarily mean you don’t love your family. It doesn’t mean you’re not grateful for the good things they gave you. It just means you need space to live your own life the way you want to live it. Women who feel no choice but to go no-contact with their dysfunctional mothers create the break because it’s the only way to send the powerful message that: ‘Mother, your life is your own responsibility as my life is mine. I refuse to be sacrificed on the altar of your pain. I refuse to be a casualty of your war. Even if you are incapable of understanding me, I must go my own way. I must choose to truly live.’”

Tara Westover, author of the harrowing childhood tale Educated, says it this way:

“You can love someone and still choose to say goodbye to them. You can miss a person every day, and still be glad that they are no longer in your life.”

Even though I never saw Mom again, I stayed in touch via telephone. I became her financial power of attorney in the last years of her life and executor of her estate after she died.

I did these things not from a sense of guilt or obligation, but because I genuinely wanted to be of service in that way to her and my siblings.

And that was the freedom of choice that my walkaway gave me.

I was enjoying a peaceful late night at work when the phone rang on the evening of October 20, 2009.

I saw the phone ID flash my sister’s name upon ringing, and I knew.

She wouldn’t call me this late otherwise.

I picked up the phone.

“Hey,” I said.

“Mom,” she said.

“Yeah?”

“She’s gone.”

We chatted for a bit, both of us in a soft state of shock.

I still don’t understand to this day how my mother died. It had something to do with a seriously botched medication schedule after colon surgery.

The hospital staff pumped her with a cocktail of Fentanyl, Dilaudid, and God knows what other medical monstrosities that caused her to aspirate her vomit.

Her death certificate listed “cardiopulminary arrest” as her cause of death. When I registered her death at the courthouse in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, the clerk glanced at the certificate and then gave me a quizzical look.

“What did your mother die of?” she asked.

“Cardiopulmonary arrest,” I responded. “That’s what the certificate says.”

“Honey,” she said, peering at me over her reading glasses, “That’s what death is. What did she die of?”

“Well I guess she died of death then,” I dryly responded.

I now say that my mother died of doctors and hospitals. Perhaps they did for her what she couldn’t do for herself.

The day after she died I felt my mother’s disembodied presence land in my living room in a swirl of shock and confusion. In the Buddhist teachings we’re taught to tell the dead person that they’ve died as a way of orienting them to their predicament.

Through my own spastic sobbing I simply repeated to her turbulent spirit, “It’s okay, Mom, you’ve died. It’s okay, Mom, you’ve died.”

I continued to talk and sing to her during the customary 49 days we Buddhists honor the dead. I felt her spirit calm down, take stock of its circumstances, and find its way forward.

In that 49-day interval my grief was completely purified. It felt clean and uncomplicated by any unfinished business. I recognized that I missed my mother more at the archetypal level than at the level of her personality.

I almost didn’t make it to her funeral.

Were it not for my boyfriend at the time agreeing to accompany me, I would have just stayed home.

Flying back with him to Philadelphia, I prepared us both to attend one of those grim, ponderous rituals you see in the movies, where three or four dry-eyed people kneel around the casket of someone whose life was riddled with unlove and misfortune.

Imagine my gob-smacked shock then, to see over 100 people show up at her memorial service.

Neighbors, friends, and community members all showed up to bid Mrs. Friel a final farewell.

“I loved your mom,” folks said to me over and over. “Yeah she was tough. I remember when she screamed at me about [some such thing or another], but I always knew she loved me.”

Listening to their words and seeing their tears, I realized with overwhelming tenderness the true tragedy of my mother’s life:

She never knew how loved she was.

Just before the casket lid was closed, we children were invited to say our final goodbyes.

When my turn came, I leaned over to kiss her forehead—that forehead I had kissed thousands of times throughout my life—that was now an alien block of ice covered with skin.

As my lips touched her frozen corpse, I heard her voice clearly say,

“Let love in, Marcella.”

The task of a lifetime. Let love in.

About a year after she died I had a very vivid dream that she had been reborn as a little girl, still physically sick but emotionally happier and more at peace.

Do I have any way to prove that? Of course not.

But as it says in the Bible, “Faith is the evidence of things unseen.”

So I choose to hold faith that despite the horrors of abuse we suffered, the lifetime my mother spent raising my siblings and me yielded enough love and enough goodness and enough merit to reroute her karmic trajectory for the better.

And if indeed, as the teachings say, I’ll be her mother in some future lifetime, I’ll welcome her back into my sphere of relations trusting that the trials of this life will have placed us both on better footing in our next go-around.

Welcome to the Heroine’s Circle!

Thank you so much for supporting my work by joining the Heroine’s Circle!

My intention in this section is to offer you some of the tools that have most helped my students and clients make the rest of their lives the best of their lives.

I’ll be offering you audios, videos, PDFs, and other tools to create a DIY workspace here where you can reap the benefits of my work at a fraction of the cost.

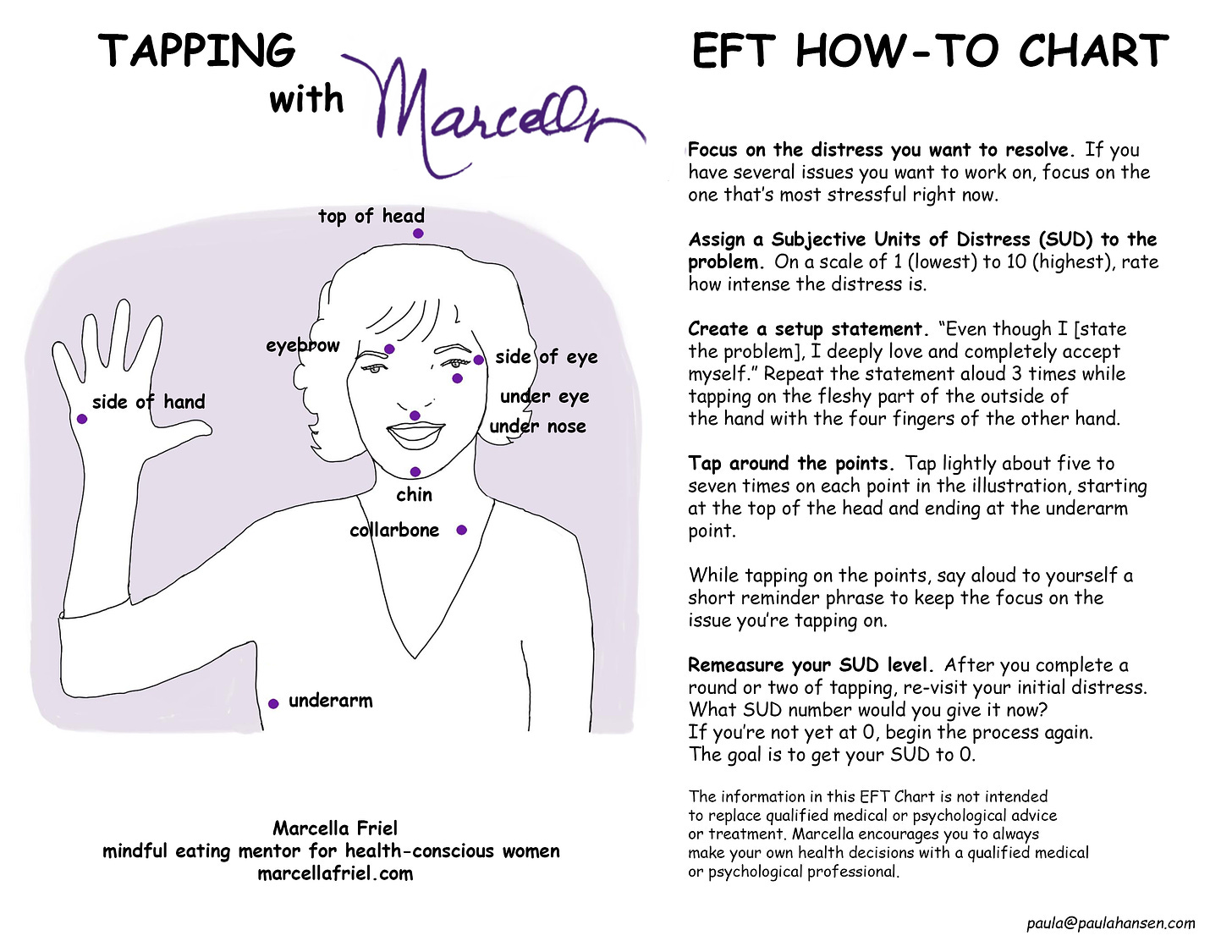

The main tool I use in my work is Tapping (you might have heard of it as EFT, Emotional Freedom Techniques, Meridian Tapping, or some other moniker).

I like to think of Tapping as positive brainwashing. It’s a simple, gentle self-help tool you can use anytime, anywhere, to reduce the negative emotional impact of memories and incidents that trigger stress.

Some folks like to call Tapping “emotional acupuncture,” as it involves fingertip tapping on points at or near the ends of major acupuncture meridians. The tapping disrupts the stress signals that link negative emotions to a particular experience.

If you’re new to Tapping, use this chart to help you get started:

Here’s a PDF version for you to print out and keep handy:

Ready to do some Tapping on your “Mom issues”?

The exercise below is a combination of EFT Tapping and non-dominant handwriting excerpted from my online course, “Healing the Mother Wound.”

(If you’d like to take that course, please use the code SUBSTACKMOM50 to save 50% on the course tuition.)

Keep repeating this exercise as necessary until you find that sweet-spot of emotional freedom.

Questions? Big shifts? Still don’t get it? I’m here for you!

Post your comments below and let me know how it goes.

XXOO

M.

Yes, telling the story “with utmost compassion“ is the way. Thank you for sharing this intimate experience and all the personal work you did to rescue yourself from resentment.

Wow Marcella, what a great story. It was especially meaningful reading it on Mother’s Day when I will call my mom and feel guilty that she is at home as well as I am at home, 150 miles away from each other.